|

|

In addition to the examples of Indian music that have been given,

especially the songs of shamans, it may be of interest to add a few

remarks concerning the several varieties of songs or chants. Songs

employed as an accompaniment to dances are known to almost all the

members of the tribe, so that their rendition is nearly always the

same. Such songs are not used in connection with mnemonic

characters, as there are, in most instances, no words or phrases

recited, but simply a continued repetition of meaningless words or

syllables. The notes are thus rhythmically accentuated, often

accompanied by beats upon the drum and the steps of the dancers.

An example of another variety of songs, or rather chants, is

presented in connection with the reception of the candidate by the

Midē´ priest upon his entrance

into the Midē´wigân of the first degree. In this instance words are

chanted, but the musical rendition differs with the individual, each

Midē´ chanting notes of his own, according to his choice or musical

ability. There is no set formula, and such songs, even if taught to

others, are soon distorted by being sung according to the taste or

ability of the singer. The musical rendering of the words and

phrases relating to the signification of mnemonic characters depends

upon the ability and inspired condition of the singer; and as each

Midē´ priest usually invents and prepares his own songs, whether for

ceremonial purposes, medicine hunting, exorcism, or any other use,

he may frequently be unable to sing them twice in exactly the same

manner. Love songs and war songs, being of general use, are always

sung in the same style of notation.

The emotions are fully expressed in the musical rendering of the

several classes of songs, which are, with few exceptions, in a minor

key. Dancing and war songs are always in quick time, the latter

frequently becoming extraordinarily animated and boisterous as the

participants become more and more excited.

Midē´ and other like songs are always more or less monotonous,

though they are sometimes rather impressive, especially if delivered

by one sufficiently emotional and possessed of a good voice. Some of

the Midē´ priests employ few notes, not exceeding a range of five,

for all songs, while others frequently cover the octave, terminating

with a final note lower still.

The statement has been made that one Midē´ is unable either to

recite or sing the proper phrase pertaining to the mnemonic

characters of a song belonging to another Midē´ unless specially

instructed. The representation of an object may refer to a variety

of ideas of a similar, though not identical, character. The picture

of a bear may signify the Bear man´idō as one of the guardians of

the society; it may pertain to the fact that the singer impersonates

that man´idō; exorcism of the malevolent bear spirit may be thus

claimed; or it may relate to the desired capture of the animal, as

when drawn to insure success for the hunter. An Indian is slow to

acquire the exact phraseology, which is always sung or chanted, of

mnemonic songs recited to him by a Midē´ preceptor.

An exact reproduction is implicitly believed to be necessary, as

otherwise the value of the formula would be impaired, or perhaps

even totally destroyed. It frequently happens, therefore, that

although an Indian candidate for admission into the Midē´wiwin may

already have prepared songs in imitation of those from which he was

instructed, he may either as yet be unable to sing perfectly the

phrases relating thereto, or decline to do so because of a want of

confidence. Under such circumstances the interpretation of a record

is far from satisfactory, each character being explained simply

objectively, the true import being intentionally or unavoidably

omitted. An Ojibwa named “Little Frenchman,” living at Red Lake, had

received almost continuous instruction for three or four years, and

although he was a willing and valuable assistant in other matters

pertaining to the subject under consideration, he was not

sufficiently familiar with some of his preceptor’s songs to fully

explain them. A few examples of such mnemonic songs are presented in

illustration, and for comparison with such as have already been

recorded. In each instance the Indian’s interpretation of the

character is given first, the notes in brackets being supplied in

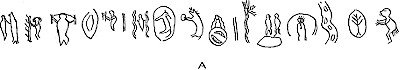

further explanation. Pl. XXII, A, is reproduced from a birch-bark

song; the incised lines are sharp and clear, while the drawing in

general is of a superior character. The record is drawn so as to be

read from right to left.

Plate XXII.a. Mnemonic Song.

|

|

From whence I sit.

[The singer is seated, as the lines indicate contact with

the surface beneath, though the latter is not shown. The

short line extending from the mouth indicates voice, and

probably signifies, in this instance, singing.]

|

|

The big tree in the center of

the earth.

[It is not known whether or not this relates to the first

destruction of the earth, when Mi´nabo´zho escaped by

climbing a tree which continued to grow and to protrude

above the surface of the flood. One Midē´ thought it related

to a particular medicinal tree which was held in estimation

beyond all others, and thus represented as the chief of the

earth.]

|

|

I will float down the fast

running stream.

[Strangely enough, progress by water is here designated by

footprints instead of using the outline of a canoe. The

etymology of the Ojibwa word used in this connection may

suggest footprints, as in the Delaware language one word for

river signifies “water road,” when in accordance therewith

“footprints” would be in perfect harmony with the general

idea.]

|

|

The place that is feared I

inhabit, the swift-running stream I inhabit.

[The circular line above the Midē´ denotes obscurity, i.e.,

he is hidden from view and represents himself as powerful

and terrible to his enemies as the water monster.]

|

|

You who speak to me. |

|

I have long horns.

[The Midē´ likens himself to the water monster, one of the

malevolent serpent man´idōs

who antagonize all good, as beliefs and practices of the

Midē´wiwin.]

|

|

A rest or pause. |

|

I, seeing, follow your example. |

|

You see my body, you see my

body, you see my nails are worn off in grasping the stone.

[The Bear man´idō is represented as the type now assumed by

the Midē´. He has a stone within his grasp, from which magic

remedies are extracted.]

|

|

You, to whom I am speaking.

[A powerful man´idō´, the panther, is in an inclosure and to

him the Midē´ addresses his request.]

|

|

I am swimming—floating—down

smoothly.

[The two pairs of serpentine lines indicate the river banks,

while the character between them is the Otter, here

personated by the Midē´.]

|

|

Bars denoting a pause. |

|

I have finished my drum.

[The Midē´ is shown holding a Midē´ drum which he is making

for use in a ceremony.]

|

|

My body is like unto you.

[The mī´gis shell, the

symbol of purity and the Midē´wiwin.]

|

|

Hear me, you who are talking to

me!

[The speaker extends his arms to the right and left

indicating persons who are talking to him from their

respective places. The lines denoting speech—or hearing—pass

through the speaker’s head to exclaim as above.]

|

|

See what I am taking.

[The Midē´ has pulled up a medicinal root. This denotes his

possessing a wonderful medicine and appears in the order of

an advertisement.]

|

|

See me, whose head is out of water. |

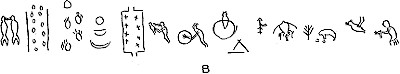

On Pl. XXII, B, is presented an illustration reproduced from a

piece of birch bark owned by the preceptor of “Little Frenchman,” of

the import of which the latter was ignorant. His idea of the

signification of the characters is based upon general information

which he has received, and not upon any pertaining directly to the

record. From general appearances the song seems to be a private 293

record pertaining to the Ghost Society, the means through which the

recorder attained his first degree of the Midē´wiwin, as well as to

his abilities, which appear to be boastfully referred to:

|

Plate XXII.b. Mnemonic Song.

|

|

I am sitting with my pipe.

[Midē´ sitting, holding his pipe. He has been called upon to

visit a patient, and the filled pipe is handed to him to

smoke preparatory to his commencing the ceremony of

exorcism.]

|

|

I employ the spirit, the spirit

of the owl.

[This evidently indicates the Owl man´idō, which has been

referred to in connection with the Red Lake Midē´ chart, Pl.

III, No. 113. The Owl man´idō is there represented as

passing from the Midē´wigân to the Dzhibai´ Midē´wigân, and

the drawings in that record and in this are sufficiently

alike to convey the idea that the maker of this song had

obtained his suggestion from the old Midē´ chart.]

|

|

It stands, that which I am

going after.

[The Midē´, impersonating the Bear man´idō, is seeking a

medicinal tree of which he has knowledge, and certain parts

of which he employs in his profession. The two footprints

indicate the direction the animal is taking.]

|

|

I, who fly.

[This is the outline of a Thunder bird, who appears to grasp

in his talons some medical plants.]

|

|

Ki´-bi-nan´ pi-zan´. Ki´binan´

is what I use, it flies like an arrow.

[The Midē´’s arm is seen grasping a magic arrow, to

symbolize the velocity of action of the remedy.]

|

|

I am coming to the earth.

[A man´idō is represented upon a circle, and in the act of

descending toward the earth, which is indicated by the

horizontal line, upon which is an Indian habitation. The

character to denote the sky is usually drawn as a curved

line with the convexity above, but in this instance the ends

of the lines are continued below, so as to unite and to

complete the ring; the intention being, as suggested by

several Midē´ priests, to denote great altitude above the

earth, i.e., higher than the visible azure sky, which is

designated by curved lines only.]

|

|

I am feeling for it.

[The Midē´ is reaching into holes in the earth in search of

hidden medicines.]

|

|

I am talking to it.

[The Midē´ is communing with the medicine man´idō´ with the

Midē´ sack, which he holds in his hand. The voice lines

extend from his mouth to the sack, which appears to be made

of the skin of an Owl, as before noted in connection with

the second character in this song.]

|

|

They are sitting round the

interior in a row.

[This evidently signifies the Ghost Lodge, as the structure

is drawn at right angles to that usually made to represent

the Midē´wigân, and also because it seems to be reproduced

from the Red Lake chart already alluded to and figured in

Pl. III, No. 112. The spirits or shadows, as the dead are

termed, are also indicated by crosses in like manner.]

|

|

You who are newly hung; you have reached half, and you are now full.

[The allusion is to three phases of the moon, probably having

reference to certain periods at which some important ceremonies or

events are to occur.]

|

|

I am going for my dish.

[The speaker intimates that he is going to make a feast, the dish

being shown at the top in the form of a circle; the footprints are

directed toward, it and signify, by their shape, that he likens

himself to the Bear man´idō, one of the guardians of the Midēwiwin.]

|

|

I go through the medicine lodge.

[The footprints within the parallel lines denote his having passed

through an unnamed number of degrees. Although the structure is

indicated as being erected like the Ghost Lodge, i.e., north and

south, it is stated that Midēwiwin is intended. This appears to be

an instance of the non-systematic manner of objective ideagraphic

delineation.]

|

|

Let us commune with one another.

[The speaker is desirous of communing with his favorite man´idōs,

with whom he considers himself on an equality, as is indicated by

the anthropomorphic form of one between whom and himself the voice

lines extend.] |

On Figs. 36-39, are reproduced several series of pictographs from

birch-bark songs found among the effects of a deceased Midē´ priest,

at Leech Lake. Reference to other relics belonging to the same

collection has been made in connection with effigies and beads

employed by Midē´ in the endeavor to prove the genuineness of their

religion and profession. These mnemonic songs were exhibited to many

Midē´ priests from various portions of the Ojibwa country, in the

hope of obtaining some satisfactory explanation regarding the import

of the several characters; but, although they were pronounced to be

“Grand Medicine,” no suggestions were offered beyond the merest

repetition of the name of the object or what it probably was meant

to represent. The direction of their order was mentioned, because in

most instances the initial character furnishes the guide. Apart from

this, the illustrations are of interest as exhibiting the superior

character and cleverness of their execution.

The initial character on Fig. 36 appears to be at the right hand

upper corner, and represents the Bear man´idō. The third figure is

that of the Midē´wiwin, with four man´idōs within it, probably the

guardians of the four degrees. The owner of the song was a Midē´ of

the second degree, as was stated in connection with his Midē´wi-gwas

or “medicine chart,” illustrated on Plate III, C.

Fig. 37 represents what appears to be a mishkiki or medicine song,

as is suggested by the figures of plants and roots. It is impossible

to state absolutely at which side the initial character is placed,

though it would appear that the human figure at the upper left hand

corner would be more in accordance with the common custom.

Fig. 38 seems to pertain to hunting, and may have been recognized as

a hunter’s chart. According to the belief of several Midē´, it is

lead from right to left, the human figure indicating the direction

according to the way in which the heads of the crane, bear, etc.,

are turned. The lower left hand figure of a man has five marks upon

the breast, which probably indicate mī´gis spots, to denote the

power of magic influence possessed by the recorder.

The characters on Fig. 39 are found to be arranged so as to read

from the right hand upper corner toward the left, the next line

continuing to the right and lastly again to the left, terminating

with the figure of a Midē´ with the mī´gis upon his breast. This is

interesting on account of the boustrophic system of delineating the

figures, and also because such instances are rarely found to occur.

This site includes some historical

materials that may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language

of a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of the

historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the WebMasters in

any way endorse the stereotypes implied. The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society, 1891

The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society

|