|

|

The Midē´wiwin—Society

of the Midē´ or

Shamans—consists of an indefinite number of Midē´

of both sexes. The society is graded into four separate and

distinct degrees, although there is a general impression

prevailing even among certain members that any degree beyond

the first is practically a mere repetition. The greater

power attained by one in making advancement depends upon the

fact of his having submitted to “being shot at with the

medicine sacks” in the hands of the officiating priests.

This may be the case at this late day in certain localities,

but from personal experience it has been learned that there

is considerable variation in the dramatization of the

ritual. One circumstance presents itself forcibly to the

careful observer, and that is that the greater number of

repetitions of the phrases chanted by the Midē´ the greater

is felt to be the amount of inspiration and power of the

performance. This is true also of some of the lectures in

which reiteration and prolongation in time of delivery aids

very much in forcibly impressing the candidate and other

observers with the importance and sacredness of the

ceremony.

It has always been customary for the Midē´ priests to

preserve birch-bark records, bearing delicate incised lines

to represent pictorially the ground plan of the number of

degrees to which the owner is entitled. Such records or

charts are sacred and are never exposed to the public view,

being brought forward for inspection only when an accepted

candidate has paid his fee, and then only after necessary

preparation by fasting and offerings of tobacco.

|

|

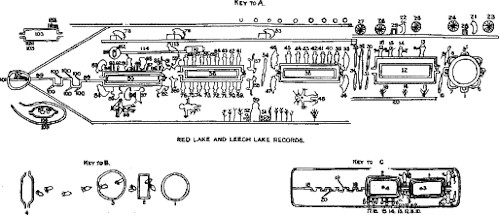

Plate III. Red Lake And Leech Lake Records (key).

Complete Plate

|

During the year 1887, while at Red Lake, Minnesota, I

had the good fortune to discover the existence of an old

birch-bark chart, which, according to the assurances of the

chief and assistant Midē´ priests, had never before been

exhibited to a white man, nor even to an Indian unless he

had become a regular candidate. This chart measures 7 feet

1½ inches in length and 18 inches in width, and is made of

five pieces of birch bark neatly and securely stitched

together by means of thin, flat strands of bass wood. At

each end are two thin strips of wood, secured transversely

by wrapping and stitching with thin strands of bark, so as

to prevent splitting and fraying of the ends of the record.

Pl. III A, is a reproduction of the design referred to.

It had been in the keeping of Skweko´mik, to whom it was

intrusted at the death of his father-in-law, the latter, in

turn, having received it in 1825 from Badâ´san, the Grand

Shaman and chief of the Winnibe´goshish Ojibwa.

It is affirmed that Badâ´san had received the original from

the Grand Midē´ priest at La Pointe, Wisconsin, where, it is

said, the Midē´wiwin was at that time held annually and the

ceremonies conducted in strict accordance with ancient and

traditional usage.

The present owner of this record has for many years used it

in the preliminary instruction of candidates. Its value in

this respect is very great, as it presents to the Indian a

pictorial résumé of the traditional history of the origin of

the Midē´wiwin, the positions occupied by the various

guardian Man´idōs in the several degrees, and the order of

procedure in study and progress of the candidate. On account

of the isolation of the Red Lake Indians and their long

continued, independent ceremonial observances, changes have

gradually occurred so that there is considerable variation,

both in the pictorial representation and the initiation, as

compared with the records and ceremonials preserved at other

reservations. The reason of this has already been given.

A detailed description of the above mentioned record, will

be presented further on in connection with two interesting

variants which were subsequently obtained at White Earth,

Minnesota. On account of the widely separated location of

many of the different bands of the Ojibwa, and the

establishment of independent Midē´ societies, portions of

the ritual which have been forgotten by one set may be found

to survive at some other locality, though at the expense of

some other fragments of tradition or ceremonial. No

satisfactory account of the tradition of the origin of the

Indians has been obtained, but such information as it was

possible to procure will be submitted.

In all of their traditions pertaining to the early history

of the tribe these people are termed A-nish´-in-â´-beg—original

people—a term surviving also among the Ottawa, Patawatomi,

and Menomoni, indicating that the tradition of their

westward migration was extant prior to the final separation

of these tribes, which is supposed to have occurred at Sault

Ste. Marie.

Mi´nabō´zho (Great Rabbit), whose name occurs in connection

with most of the sacred rites, was the servant of Dzhe

Man´idō, the Good Spirit, and acted in the capacity of

intercessor and mediator. It is generally supposed that it

was to his good offices that the Indian owes life and the

good things necessary to his health and subsistence.

The tradition of Mi´nabō´zho and the origin of the

Midē´wiwin, as given in connection with the birch-bark

record obtained at Red Lake (Pl. III A), is as follows:

When Mi´nabō´zho, the servant of Dzhe Man´idō, looked down

upon the earth he beheld human beings, the Ani´shinâ´beg,

the ancestors of the Ojibwa. They occupied the four quarters

of the earth—the northeast, the southeast, the southwest,

and the northwest. He saw how helpless they were, and

desiring to give them the means of warding off the diseases

with which they were constantly afflicted, and to provide

them with animals and plants to serve as food and with other

comforts, Mi´nabō´zho remained thoughtfully hovering over

the center of the earth, endeavoring to devise some means of

communicating with them, when he heard something laugh, and

perceived a dark object appear upon the surface of the water

to the west (No. 2). He could not recognize its form, and

while watching it closely it slowly disappeared from view.

It next appeared in the north (No. 3), and after a short

lapse of time again disappeared. Mi´nabō´zho hoped it would

again show itself upon the surface of the water, which it

did in the east (No. 4). Then Mi´nabō´zho wished that it

might approach him, so as to permit him to communicate with

it. When it disappeared from view in the east and made its

reappearance in the south (No. 1), Mi´nabō´zho asked it to

come to the center of the earth that he might behold it.

Again it disappeared from view, and after reappearing in the

west Mi´nabō´zho observed it slowly approaching the center

of the earth (i.e., the centre of the circle), when he

descended and saw it was the Otter, now one of the sacred

Man´idōs of the Midē´wiwin. Then Mi´nabō´zho instructed the

Otter in the mysteries of the Midē´wiwin, and gave him at

the same time the sacred rattle to be used at the side of

the sick; the sacred Midē´ drum to be used during the

ceremonial of initiation and at sacred feasts, and tobacco,

to be employed in invocations and in making peace.

The place where Mi´nabō´zho descended was an island in the

middle of a large body of water, and the Midē´ who is feared

by all the others is called Mini´sino´shkwe

(He-who-lives-on-the-island). Then Mi´nabō´zho built a

Midē´wigân (sacred Midē´ lodge), and taking his drum he beat

upon it and sang a Midē´ song, telling the Otter that Dzhe

Man´idō had decided to help the Aníshinâ´bog, that they

might always have life and an abundance of food and other

things necessary for their comfort. Mi´nabō´zho then took

the Otter into the Midē´wigân and conferred upon him the

secrets of the Midē´wiwin, and with his Midē´ bag shot the

sacred mī´gis into his body that he might have immortality

and be able to confer these secrets to his kinsmen, the

Aníshinâ´beg.

The mī´gis is considered the sacred symbol of the Midē´wigân,

and may consist of any small white shell, though the one

believed to be similar to the one mentioned in the above

tradition resembles the cowrie, and the ceremonies of

initiation as carried out in the Midē´wiwin at this day are

believed to be similar to those enacted by Mi´nabō´zho and

the Otter. It is admitted by all the Midē´ priests whom I

have consulted that much of the information has been lost

through the death of their aged predecessors, and they feel

convinced that ultimately all of the sacred character of the

work will be forgotten or lost through the adoption of new

religions by the young people and the death of the Midē´

priests, who, by the way, decline to accept Christian

teachings, and are in consequence termed “pagans.”

My instructor and interpreter of the Red Lake chart added

other information in explanation of the various characters

represented thereon, which I present herewith. The large

circle at the right side of the chart denotes the earth as

beheld by Mi´nabō´zho, while the Otter appeared at the

square projections at Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4; the semicircular

appendages between these are the four quarters of the earth,

which are inhabited by the Ani´shinâ´beg, Nos. 5, 6, 7, and

8. Nos. 9 and 10 represent two of the numerous malignant

Man´idōs, who endeavor to prevent entrance into the sacred

structure and mysteries of the Midē´wiwin. The oblong

squares, Nos. 11 and 12, represent the outline of the first

degree of the society, the inner corresponding lines being

the course traversed during initiation. The entrance to the

lodge is directed toward the east, the western exit

indicating the course toward the next higher degree. The

four human forms at Nos. 13, 14, 15, and 16 are the four

officiating Midē´ priests whose services are always demanded

at an initiation. Each is represented as having a rattle.

Nos. 17, 18, and 19 indicate the cedar trees, one of each of

this species being planted near the outer angles of a Midē´

lodge. No. 20 represents the ground. The outline of the bear

at No. 21 represents the Makwa´ Man´idō, or Bear Spirit, one

of the sacred Midē´ Man´idōs, to which the candidate must

pray and make offerings of tobacco, that he may compel the

malevolent spirits to draw away from the entrance to the

Midē´wigân, which is shown in No. 28. Nos 23 and 24

represent the sacred drum which the candidate must use when

chanting the prayers, and two offerings must be made, as

indicated by the number two.

After the candidate has been admitted to one degree, and is

prepared to advance to the second, he offers three feasts,

and chants three prayers to the Makwa´ Man´idō, or Bear

Spirit (No. 22), that the entrance (No. 29) to that degree

may be opened to him. The feasts and chants are indicated by

the three drums shown at Nos. 25, 26, and 27.

Nos. 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34 are five Serpent Spirits, evil

Man´idōs who oppose a Midē´’s progress, though after the

feasting and prayers directed to the Makwa´ Man´idō have by

him been deemed sufficient the four smaller Serpent Spirits

move to either side of the path between the two degrees,

while the larger serpent (No. 32) raises its body in the

middle so as to form an arch, beneath which passes the

candidate on his way to the second degree.

Nos. 35, 36, 46, and 47 are four malignant Bear Spirits, who

guard the entrance and exit to the second degree, the doors

of which are at Nos. 37 and 49. The form of this lodge (No.

38) is like the preceding; but while the seven Midē´ priests

at Nos. 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, and 45 simply indicate that

the number of Midē´ assisting at this second initiation are

of a higher and more sacred class of personages than in the

first degree, the number designated having reference to

quality and intensity rather than to the actual number of

assistants, as specifically shown at the top of the first

degree structure.

When the Midē´ is of the second degree, he receives from

Dzhe Man´idō supernatural powers as shown in No. 48. The

lines extending upward from the eyes signify that he can

look into futurity; from the ears, that he can hear what is

transpiring at a great distance; from the hands, that he can

touch for good or for evil friends and enemies at a

distance, however remote; while the lines extending from the

feet denote his ability to traverse all space in the

accomplishment of his desires or duties. The small disk upon

the breast of the figure denotes that a Midē´ of this degree

has several times had the mī´gis—life—“shot into his body,”

the increased size of the spot signifying amount or quantity

of influence obtained thereby.

No. 50 represents a Mi´tsha Midē´ or Bad Midē´, one who

employs his powers for evil purposes. He has the power of

assuming the form of any animal, in which guise he may

destroy the life of his victim, immediately after which he

resumes his human form and appears innocent of any crime.

His services are sought by people who wish to encompass the

destruction of enemies or rivals, at however remote a

locality the intended victim may be at the time. An

illustration representing the modus operandi of his

performance is reproduced and explained in Fig. 24, page

238.

Persons possessed of this power are sometimes termed

witches, special reference to whom is made elsewhere. The

illustration, No. 50, represents such an individual in his

disguise of a bear, the characters at Nos. 51 and 52

denoting footprints of a bear made by him, impressions of

which are sometimes found in the vicinity of lodges occupied

by his intended victims. The trees shown upon either side of

No. 50 signify a forest, the location usually sought by bad

Midē´ and witches.

If a second degree Midē´ succeeds in his desire to become a

member of the third degree, he proceeds in a manner similar

to that before described; he gives feasts to the instructing

and four officiating Midē´, and offers prayers to Dzhe

Man´idō for favor and success. No. 53 denotes that the

candidate now personates the bear—not one of the malignant

Man´idōs, but one of the sacred Man´idōs who are believed to

be present during the ceremonials of initiation of the

second degree. He is seated before his sacred drum, and when

the proper time arrives the Serpent Man´idō (No. 54)—who has

until this opposed his advancement—now arches its body, and

beneath it he crawls and advances toward the door (No. 55)

of the third degree (No. 56) of the Midē´wiwin, where he

encounters two (Nos. 57 and 58) of the four Panther Spirits,

the guardians of this degree.

Nos. 61 to 76 indicate Midē´ spirits who inhabit the

structure of this degree, and the number of human forms in

excess of those shown in connection with the second degree

indicates a correspondingly higher and more sacred

character. When an Indian has passed this, initiation he

becomes very skillful in his profession of a Midē´. The

powers which he possessed in the second degree may become

augmented. He is represented in No. 77 with arms extended,

and with lines crossing his body and arms denoting darkness

and obscurity, which signifies his ability to grasp from the

invisible world the knowledge and means to accomplish

extraordinary deeds. He feels more confident of prompt

response and assistance from the sacred Man´idōs and his

knowledge of them becomes more widely extended.

|

This site includes some historical

materials that may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language

of a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of the

historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the WebMasters in

any way endorse the stereotypes implied. The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society, 1891

The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society

| Next

|