|

|

After this song is ended the drum is handed to one of the members

sitting near by, when the fourth and last of the officiating priests

says to the candidate, who is now placed upon his knees:

| Mis-sa´-a-shi´-gwa |

ki-bo´-gis-se-na-min |

tshi´-ma-mâd |

| Now is the time |

that I hope of you |

that you shall

|

| bi-mâ´-di-si-win, |

mi-ne´-sid. |

| take life |

the bead [mī´gis shell.] |

This priest then grasps his Midē´ sack as if holding a gun, and,

clutching it near the top with the left hand extended, while with

the right he clutches it below the middle or near the base, he aims

it toward the candidate’s left breast and makes a thrust forward

toward that target uttering the syllables “yâ, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´,” rapidly, rising to a

higher key. He recovers his first position and repeats this movement

three times, becoming more and more animated, the last time making a

vigorous gesture toward the kneeling man’s breast as if shooting

him. (See Fig. 15, page 192.) While this is going on, the preceptor

and his assistants place their hands upon the candidate’s shoulders

and cause his body to tremble.

Then the next Midē´, the third of the quartette, goes through a

similar series of forward movements and thrusts with his Midē´ sack,

uttering similar sounds and shooting the sacred mī´gis—life—into

the right breast of the candidate, who is agitated still more

strongly than before. When the third Midē´, the second in order of

precedence, goes through similar gestures and pretends to shoot the

mī´gis into the candidate’s heart, the preceptors assist him to be

violently agitated.

The leading priest now places himself in a threatening attitude and

says to the Midē´; “Mi´-dzhi-de´-a-mi-shik´”—“put your helping heart

with me”—, when he imitates his predecessors by saying, “yâ, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´,” at the fourth time aiming

the Midē´ sack at the candidate’s head, and as the mī´gis is

supposed to be shot into it, he falls forward upon the ground,

apparently lifeless.

Then the four Midē´ priests, the preceptor and the assistant, lay

their Midē´ sacks upon his back and after a few moments a mī´gis

shell drops from his mouth—where he had been instructed to retain

it. The chief Midē´ picks up the mī´gis and, holding it between the

thumb and index finger of the right hand, extending his arm toward

the candidate’s mouth says “wâ! wâ! he he he he,” the last syllable

being uttered in a high key and rapidly dropped to a low note; then

the same words are uttered while the mī´gis is held toward the east,

and in regular succession to the south, to the west, to the north,

then toward the sky. During this time the candidate has begun to

partially revive and endeavor to get upon his knees, but when the

Midē´ finally places the mī´gis into his mouth again, he instantly

falls upon the ground, as before. The Midē´ then take up the sacks,

each grasping his own as before, and as they pass around the

inanimate body they touch it at various points, which causes the

candidate to “return to life.” The chief priest then says to him,

“O´mishga‘n”1—“get up”—which he does; then indicating to the holder

of the Midē´ drum to bring that to him, he begins tapping and

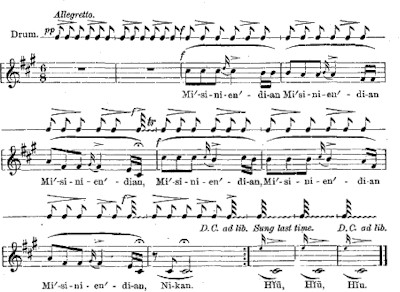

presently sings the following song:

|

|

Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an Mi´si-ni-en´-di-an Mi´-si-ni-en´-dian,

Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an, Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an,

Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an, Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an Mi´-si-ni-en´-di-an,

Ni-kan. Hĭū, Hĭū,

Hĭū.

The words of the text signify, “This is what I am, my fellow Midē´;

I fear all my fellow Midē´.” The last syllables, hĭū´,

are meaningless.

At the conclusion of the song the preceptor prompts the candidate to

ask the chief Midē´:

| Ni-kan´ |

k´kĕ´-nō´-mo´, |

man-dzhi´-an |

na´-ka-mō´-in. |

| Colleague |

instruct me, |

give me |

a song. |

In response to which the Midē´ teaches him the following, which

is uttered as a monotonous chant, viz:

| We´-go-nĕn´ |

ge-gwed´-dzhi-me-an´, |

mi-dē´-wi-wĭn |

ke-kwed´-dzhi-me-an´? |

| What |

are you asking, |

grand medicine |

are you asking?

|

| Ki´-ka-mi´-nin |

en-da-wĕn´-da |

ma-wi´-nĕn |

mi-dē´-wi-wĭn |

| I will give you |

you want me to |

give you |

“grand medicine”

|

| tshi-da-si-nē´-ga´-na-win´-da-mōn; |

ki-ĭn´-tshun-di´-nĕ-ma´-so-wĭn, |

| always take care

of; |

you have

received it yourself,

|

| tsho´-a-wa´-nin |

di´-sĕ-wan. |

| never |

forget. |

To this the candidate, who is now a member, replies,

ēn, yes, i.e.,

assent, fully agreeing with the statement made by the Midē´, and

adds:

| Mi-gwetsh´ |

a-shi´-wa-ka-kish´-da-win |

be-mâ´-di-si´-an. |

| Thanks |

for giving to me |

life. |

Then the priests begin to look around in search of spaces in

which to seat themselves, saying:

| Mi´-a-shi´-gwa

ki´-tshi-an´-wâ-bin-da-man |

tshi-o´-we-na´-bi-an. |

| Now is the time I look

around |

where we shall be [sit]. |

and all go to such places as are made, or reserved, for them.

The new member then goes to the pile of blankets, robes, and other

gifts and divides them among the four officiating priests, reserving

some of less value for the preceptor and his assistant; whereas

tobacco is carried around to each person present. All then make an

offering of smoke, to the east, south, west, north, toward the

center and top of the Midē´wigân—where Ki´tshi Man´idō presides—and

to the earth. Then each person blows smoke upon his or her Midē´

sack as an offering to the sacred mī´gis within.

The chief Midē´ advances to the new member and presents him with a

new Midē´ sack, made of an otter skin, or possibly of the skin of

the mink or weasel, after which he returns to his place. The new

member rises, approaches the chief Midē´, who inclines his head to

the front, and, while passing both flat hands down over either side,

| Mi-gwetsh´, |

ni-ka´-ni, ni-ka´-ni,

ni-ka´-ni, na-ka´. |

| Thanks, |

my colleagues, my

colleagues, my colleagues. |

Then, approaching the next in rank, he repeats the ceremony and

continues to do so until he has made the entire circuit of the

Midē´wigân.

At the conclusion of this ceremony of rendering thanks to the

members of the society for their presence, the newly elected Midē´

returns to his place and, after placing within his Midē´ sack his

mī´gis, starts out anew to test his own powers. He approaches the

person seated nearest the eastern entrance, on the south side, and,

grasping his sack in a manner similar to that of the officiating

priests, makes threatening motions toward the Midē´ as if to shoot

him, saying, “yâ, hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´,” gradually raising his

voice to a higher key. At the fourth movement he makes a quick

thrust toward his victim, whereupon the latter falls forward upon

the ground. He then proceeds to the next, who is menaced in a

similar manner and who likewise becomes apparently unconscious from

the powerful effects of the mī´gis. This is continued until all

persons present have been subjected to the influence of the mī´gis

in the possession of the new member. At the third or fourth

experiment the first subject revives and sits up, the others

recovering in regular order a short time after having been “shot

at,” as this procedure is termed.

When all of the Midē´ have recovered a very curious ceremony takes

place. Each one places his mī´gis shell upon the right palm and,

grasping the Midē´ sack with the left hand, moves around the

inclosure and exhibits his mī´gis to everyone present, constantly

uttering the word “hŏ´, hŏ´,

hŏ´, hŏ´,”

in a quick, low tone. During this period there is a mingling of all

the persons present, each endeavoring to attract the attention of

the others. Each Midē´ then pretends to swallow his mī´gis, when

suddenly there are sounds of violent coughing, as if the actors were

strangling, and soon thereafter they gag and spit out upon the

ground the mī´gis, upon which each one falls apparently dead. In a

few moments, however, they recover, take up the little shells again

and pretend to swallow them. As the Midē´ return to their respective

places the mī´gis is restored to its receptacle in the Midē´ sack.

Food is then brought into the Midē´wigân and all partake of it at

the expense of the new member.

After the feast, the older Midē´ of high order, and possibly the

officiating priests, recount the tradition of the Ani´shinâ´bēg

and the origin of the Midē´wiwin, together with speeches relating to

the benefits to be derived through a knowledge thereof, and

sometimes, tales of individual success and exploits. When the

inspired ones have given utterance to their thoughts and feelings,

their memories and their boastings, and the time of adjournment has

almost arrived, the new member gives an evidence of his skill as a

singer and a Midē´. Having acted upon the suggestion of his

preceptor, he has prepared some songs and learned them, and now for

the first time the opportunity presents itself for him to gain

admirers and influential friends, a sufficient number of whom he

will require to speak well of him, and to counteract the evil which

will be spoken of him by enemies—for enemies are numerous and may be

found chiefly among those who are not fitted for the society of the

Midē´, or who have failed to attain the desired distinction.

The new member, in the absence of a Midē´ drum of his own, borrows

one from a fellow Midē´ and begins to beat it gently, increasing the

strokes in intensity as he feels more and more inspired, then sings

a song (Pl. X, D), of which the following are the words, each line

being repeated ad libitum, viz:

|

Plate X.d. Mnemonic Song.

|

|

We´-nen-wi´-wik ka´-ni-an.

The spirit has made sacred the place in which I live.

The singer is shown partly within, and partly above his

wigwam, the latter being represented by the lines upon

either side, and crossing his body.

|

|

En´-da-yan´ pi-ma´-ti-sŭ´-i-un

en´-da-yan´.

The spirit gave the “medicine” which we receive.

The upper inverted crescent is the arch of the sky, the

magic influence descending, like rain upon the earth, the

latter being shown by the horizontal line at the bottom.

|

|

Rest. |

|

Nin´-nik-ka´-ni man´-i-dō.

I too have taken the medicine he gave us.

The speaker’s arm, covered with mī´gis, or magic influence,

reaches toward the sky to receive from Ki´tshi Man´idō the

divine favor of a Mide’s power.

|

|

Ke-kĕk´-ō-ĭ-yan´.

I brought life to the people.

The Thunderer, the one who causes the rains, and

consequently life to vegetation, by which the Indian may

sustain life.

|

|

Be-mo´-se ma-kō-yan.

I have come to the medicine lodge also.

The Bear Spirit, one of the guardians of the Midē´wiwin, was

also present, and did not oppose the singer’s entrance.

|

|

Ka´-ka-mi´-ni-ni´-ta.

We spirits are talking together.

The singer compares himself and his colleagues to spirits,

i.e., those possessing supernatural powers, and communes

with them as an equal.

|

|

O-ni´-ni-shĭnk-ni´-yo.

The mī´gis is on my body.

The magic power has been put into his body by the Mide

priests.

|

|

Ni man´-i-dō

ni´-yăn.

The spirit has put away all my sickness.

He has received new life, and is, henceforth, free from the

disturbing influences of evil Man´idōs. |

As the sun approaches the western horizon, the Midē´ priests

emerge from the western door of the Midē´wigân and go to their

respective wig´iwams, where they partake of their regular evening

repast, after which the remainder of the evening is spent in paying

calls upon other members of the society, smoking, etc.

The preceptor and his assistant return to the Midē´wigân at

nightfall, remove the degree post and plant it at the head of the

wig´iwam—that part directly opposite the entrance—occupied by the

new member. Two stones are placed at the base of the post, to

represent the two forefeet of the bear Man´idō through whom life was

also given to the Ani´shinâ´bēg.

If there should be more than one candidate to receive a degree the

entire number, if not too great, is taken into the Midē´wigân for

initiation at the same time; and if one day suffices to transact the

business for which the meeting was called the Indians return to

their respective homes upon the following morning. If, however,

arrangements have been made to advance a member to a higher degree,

the necessary changes and appropriate arrangement of the interior of

the Midē´wigân are begun immediately after the society has

adjourned.

1 The chief priest then says to him,

“Ō´mishga‘n”—“get up”—which he does

The backward apostrophe in Ō´mishga‘n

occurs nowhere else in the text; it may be phonetic (glottal stop?)

or an error.

This site includes some historical

materials that may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language

of a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of the

historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the WebMasters in

any way endorse the stereotypes implied. The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society, 1891

Previous

| The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society

| Next

|