|

|

While it is customary among many tribes of Indians to use as

little clothing as possible when engaged in dancing, either of a

social or ceremonial nature, the Ojibwa, on the contrary, vie with

one another in the attempt to appear in the most costly and gaudy

dress attainable. The Ojibwa Midē´

priests, take particular pride in their appearance when attending

ceremonies of the Midē´ Society, and seldom fail to impress this

fact upon visitors, as some of the Dakotan tribes, who have adopted

similar medicine ceremonies after the custom of their Algonkian

neighbors, are frequently without any clothing other than the

breechcloth and moccasins, and the armlets and other attractive

ornaments. This disregard of dress appears, to the Ojibwa, as a

sacrilegious digression from the ancient usages, and it frequently

excites severe comment.

Apart from facial ornamentation, of such design as may take the

actor’s fancy, or in accordance with the degree of which the subject

may be a member, the Midē´ priests wear shirts, trousers, and

moccasins, the first two of which may consist of flannel or cloth

and be either plain or ornamented with beads, while the latter are

always of buckskin, or, what is more highly prized, moose skin,

beaded or worked with colored porcupine quills.

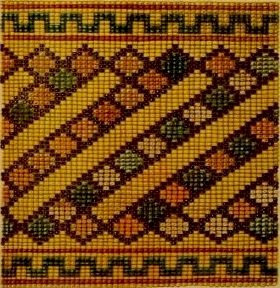

| Immediately below each knee is tied a necessary item of

an Ojibwa’s dress, a garter, which consists of a band of

beads varying in different specimens from 2 to 4 inches in

width, and from 18 to 20 inches in length, to each end of

which strands of colored wool yarn, 2 feet long, are

attached so as to admit of being passed around the leg and

tied in a bow-knot in front. These garters are made by the

women in such patterns as they may be able to design or

elaborate. On Pl. XXIII are reproductions of parts of two

patterns which are of more than |

Plate XXIII. Midē´ Dancing Garters. |

|

| ordinary interest, because of the symbolic

signification of the colors and the primitive art design in

one, and the substitution of colors and the introduction of

modern designs in the other. The upper one consists of

green, red, and white beads, the first two colors being in

accord with those of one of the degree posts, while the

white is symbolical of the mī´gis

shell. In the lower illustration is found a substitution of

color for the preceding, accounted for by the Midē´

informants, who explained that neither of the varieties of

beads of the particular color desired could be obtained when

wanted. The yellow beads are substituted for white, the blue

for green, and the orange and pink for red. The design

retains the lozenge form, though in a different arrangement,

and the introduction of the blue border is adapted after

patterns observed among their white neighbors. In the former

is presented also what the Ojibwa term the groundwork or

type of their original style of ornamentation, i.e., wavy or

gently zigzag lines. Later art work consists chiefly of

curved lines, and this has gradually become modified through

instruction from the Catholic sisters at various early

mission establishments until now, when there has been

brought about a common system of working upon cloth or

velvet, in patterns, consisting of vines, leaves, and

flowers, often exceedingly attractive though not aboriginal

in the true sense of the word. |

Bands of flannel or buckskin, handsomely beaded, are sometimes

attached to the sides of the pantaloons, in imitation of an

officer’s stripes, and around the bottom. Collars are also used, in

addition to necklaces of claws, shells, or other objects.

Armlets and bracelets are sometimes made of bands of beadwork,

though brass wire or pieces of metal are preferred.

Bags made of cloth, beautifully ornamented or entirely covered with

beads, are worn, supported at the side by means of a broad band or

baldric passing over the opposite shoulder. The head is decorated

with disks of metal and tufts of colored horse hair or moose hair

and with eagle feathers to designate the particular exploits

performed by the wearer.

Few emblems of personal valor or exploits are now worn, as many of

the representatives of the present generation have never been

actively engaged in war, so that there is generally found only among

the older members the practice of wearing upon the head eagle

feathers bearing indications of significant markings or cuttings. A

feather which has been split from the tip toward the middle denotes

that the wearer was wounded by an arrow. A red spot as large as a

silver dime painted upon a feather shows the wearer to have been

wounded by a bullet. The privilege of wearing a feather tipped with

red flannel or horse hair dyed red is recognized only when the

wearer has killed an enemy, and when a great number have been killed

in war the so-called war bonnet is worn, and may consist of a number

of feathers exceeding the number of persons killed, the idea to be

expressed being “a great number,” rather than a specific

enumeration.

Although the Ojibwa admit that in former times they had many other

specific ways of indicating various kinds of personal exploits, they

now have little opportunity of gaining such distinction, and

consequently the practice has fallen into desuetude.

This site includes some historical

materials that may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language

of a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of the

historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the WebMasters in

any way endorse the stereotypes implied. The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society, 1891

The Midē Wiwin or Grand Medicine Society

|